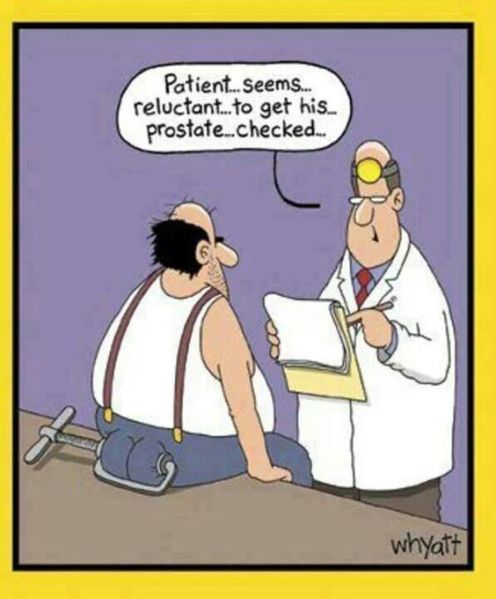

It seems like all my male friends have had biopsies of the prostate, and not wanting to miss out on something special, I arranged to join the club. I picked a hot Friday in July. The forecast was 110 for Tucson, too hot to work in the yard or go birding; a perfect day to hang out at the local urology clinic. I arrived early and had just started a Newsweek article about Obama’s first election when they called my name. The clinic’s thermostat was set at deep space, but I broke into a shirt-staining sweat as I followed Mary to Room Number Four. Mary smiled, told me to take off all my clothes from the waist down and lie on a cot that was covered by a large maxi-pad.

“Face the wall and assume the fetal position”, she said.

“That won’t be hard”, I answered. “I drove all the way here in the fetal position.” She left the room, telling me they would be back in a few minutes. Time creeped, giving me second, third and fourth thoughts. Finally the door opened. Facing the wall, I couldn’t see how many of ‘they’ were there, but my doctor leaned into my vision, smiled and apologized for the delay. He looked calm and competent, experienced and kind. The look of a trained CIA professional. He told me he would explain everything in detail as the procedure progressed, which in hindsight I should have declined.

The first step, he said, was to insert an ultrasound probe so he could ‘map’ my prostate gland. He told me I would notice that the probe was larger than the finger he had used on an earlier digital exam. He was right. At first, I thought he had mistakenly chosen a broomstick instead of the probe, but then I realized it was probably a Louisville Slugger baseball bat, inserted from the large end. He hummed ‘Take me out to the ballgame’ while he maneuvered the probe around, seemingly mapping the southern hemisphere. I squirmed and sweat baseball-sized bullets.

Apparently this was not considered painful, since he finished mapping before injecting pain killers. “Now I’m going to inject lidocaine into one side of your prostate”, he said. “You’ll feel a sharp stabbing pain followed by a diminishing aching pain.” He was right. “Now we’ll repeat that on the other side of the prostate, and you’ll feel the same thing.” He was right again.

He asked someone I couldn’t see to hand him the sampling needle. “This may be a little uncomfortable, but it shouldn’t hurt much”, he said. “You’ll hear a snapping sound as I collect each tissue sample, twelve in all.” My friends had told me this sound reminds you of a staple gun or an empty BB gun, but the needle is a 16 gauge, which suggests a shotgun. This tool is called a ‘soft tissue biopsy system’, is spring-loaded and when triggered by the doctor, fires the needle through the rectum wall and into the prostate gland to collect a tissue sample. The needle itself is 9 centimeters long, well on its way to 4 inches. The online description features ‘one handed operation’ and ‘automatic spring-loaded for fast, accurate penetration.’ It’s a one-use device for sale at less than 500 bucks, so if you were a masochist, I guess you could try this on yourself at home. After the first fast and accurate penetration, the assistant reloads and the doctor moves to the next target area and fires again. I lay there imagining I was at the battle of the Alamo and wishing Santa Anna would get it over.

I lost count, but the doctor told me he had decided to get 14 samples instead of 12. Afterward, he explained the post procedure instructions and what to expect, most of which had to do with blood and bleeding. One of the reasons given to call the doctor was if you experienced ‘heavy bleeding.’ Bleeding from various sources could be expected for up to months, but ‘heavy’ bleeding was cause for concern. I asked him how I would know the difference. He said when I look at the blood, if I asked myself “I wonder if that’s heavy bleeding”, it isn’t. But he said, “If you take a look and think Holy shit, that’s a LOT of blood, call the office.”

In the fall of 1976, before I became “old”, my good friend, Bud, whose passion was betting on horse races, told me that I had a namesake. Not someone he had run into at the track, but a horse. And not just any horse, but a semi-famous stallion thoroughbred which, at that time, held the Bay Meadows track record for the mile and one-eighth, and had held it since October, 1968. “Ole Bob Bowers” was the horse’s name, and as proof, Bud produced a photocopy of what appeared to be a racing form, listing all the current Bay Meadows track records. All of my friends were expert practical jokers, so I laughed this off and turned to more important things, like wine tasting. I knew nothing about horse racing, but I knew that horses had blood-stirring names like Man O’ War, Bold Ruler or Seabiscuit, and that Bud’s little list was obviously a joke.

But I kept it anyway, since it made good cocktail party conversation, and eventually I filed it away with other junk from the seventies. There it sat until 2006, when an invitation to a Kentucky Derby party stirred old memories. Barbaro won that race and I started thinking about thoroughbred names again. I found the old photocopy and decided to Google the name, and, mother of all surprises, Ole Bob Bowers was revealed in all his glory. Bud had not been joking after all. Not only had Ole Bob been a record holder, he had even been a stakes winner at Tanforan.

Ole Bob was a bit of a sexy beast, as well, siring a passel of ninety progeny, some that seem weirdly appropriate, like Ole Bow Wower, Joyfull Jumper, Boozie Trip, Chase the Nurse and No Work Today. Two others are even more strangely connected—Charjo Jenny (I have a daughter, Jenny) and Lucies Bower (I have a cousin, Lucy). But his track and stud muffin accomplishments fade when compared with one of those many offspring, John Henry. Like the folk-hero steel driving man he must have been named after, John Henry was a legendary, rags to riches horse that gives me a weird sense of fatherly pride. The Internet is full of stories and news of John Henry, who turned 31 at the Kentucky Horse Park on March 9, 2006. That’s 101 in human years. John was a feisty horse, to put it mildly, leading to an early castration. Although this didn’t improve his attitude, it might have let him focus more on his racing. He went on to an incredible career, winning 39 of 83 races and placing second or third another 24 times. He was named horse of the year twice, won seven coveted Eclipse Awards and, at six and a half million dollars, was the record money winner for years. Makes a daddy proud.

The publications are less kind to Ole Bob, in spite of the fact that he was a stakes winner, equaled the world record for nine furlongs and had more kids than a fundamentalist Mormon. One writer called him “ranker than dog shit in the stud and a below average producer.” Really? Another writer, talking about John Henry, said that “he was sired by a rather mediocre stallion known more for his terrible, terrible temperament than for his racing or sire ability. Ole Bob was such a nasty candidate that he’d been sold as a stallion for a mere nine hundred dollars.” I’m feeling personally insulted.

I never discovered how Ole Bob got his name. Horse names often bear connections to their parentage, but Ole Bob’s “parents” were Prince Blessed and Blue Jeans. Prince Blessed came from Princequillo and Dog Blessed and Princequillo came from Prince Rose and Cosquilla. “Old Prince Bob” might have been a more appropriate name.

Blood-stirring or not, you can have your Battle Joined, Man O’ War and Seabiscuit. My favorite is Ole Bob Bowers, and I’m looking forward to the movie.

All in all, I did fairly well with the results of my last six-in-one-day biopsies. Four were benign, and the prospect of undergoing simultaneous surgery on two didn’t seem insurmountable, so I agreed to a twofer, and scheduled it for last Monday. One of the two was diagnosed as a basal cell carcinoma, on my cheek to the right of my nose, a simple-looking small pearly bump. The other was identified as a squamous cell carcinoma, more worrisome due to the potential for metastasis. This one was on my forehead, just right of center. These two represented numbers seven and eight of my ongoing issue with skin cancers. Strangely, all eight have been on the right side of my body.

When it comes to skin cancer surgery, you basically have two options, regular old-fashioned surgery (surgical excision) or the more sophisticated-sounding Mohs surgery. Given a choice, I opt for Mohs, since it is less invasive and leaves less damage to repair.

Mohs surgery, short for Mohs micrographic surgery, is named for the doctor who first developed the technique, Frederic Mohs. If the non-Mohs option of surgical excision is used, the surgeon removes visible cancer and adds a comfortable (to him) margin of healthy surrounding tissue in an attempt to insure the elimination of cancer and a possible recurrence. By contrast, Mohs surgery involves a smaller initial tissue removal followed by microscopic mapping and examination of the excised section while the patient waits. If the section’s margins are free of cancer, the procedure is over and the wound is closed. If cancer is still present at any point on the section’s margins, additional surgery is performed, but limited to those areas alone, and again limited in scope. The second excised section is then mapped and examined microscopically while the patient once more waits. This process, which might take several surgeries and microscopic analyses, continues until all margins are clear. For the patient, this could mean a longer morning with multiple anesthetic injections and surgeries, but the results, compared with standard surgical excision, will probably be a smaller wound and scar, coupled with a low probability of recurrence.

In my case last week, when I returned to the doctor after an hour’s wait for results of the first surgery, I found that the forehead squamous cell margins were clear, but not so for the basal cell on my cheek. No more surgery was required on my forehead, but the doctor had to excise more tissue from the cheek wound. Another round of anesthetic injections were required, followed by a short second slicing, and then it was back to the waiting room for another hour. This second attempt also was not completely successful, so a third round was necessary, followed by another, near two-hour, wait for results. This third time proved to be the charm. The wound, however, was now quarter-sized, and it took almost an hour to put both holes back together. As she said goodbye, the doctor pointed out a couple of new spots to ‘keep an eye on.’

This isn’t fun, not near as fun as all that time, long ago, in the sun, but the piper does have to be paid. If you’ve had Mohs surgery, donated a slow pound of flesh and complained, just be thankful you weren’t one of Dr. Mohs’ early patients. Back in the 1930’s, when he first performed this procedure, it was called ‘chemosurgery’ because it involved the use of a chemical, zinc chloride. Mohs had discovered that zinc chloride could ‘fix’ skin tissue for microscopic study, so he first applied a paste of the stuff, allowing excision without bleeding. This was an involved process that often took days, rather than hours, and caused ‘severe discomfort’ to the patient. In 1953, Mohs had a patient with a basal cell carcinoma on his eyelid. To avoid risk to the eye, Mohs skipped the chemical paste step and discovered the results were equally successful. And with a lot less discomfort. I’m not complaining anymore.

On Monday of this week, President Obama announced planned trade sanctions against China. Three days later, I made the mistake of keeping an appointment with Doctor Wu, my Chinese dermatologist. Don’t get me wrong, I really love this lady. She’s the best Mohs surgeon I’ve ever known, and I’ve been sliced and diced by more than my share. On the other hand, my timing might have been off, what with this China thing.

I did have one little suspicious-looking spot under my right eye, but figured a quick and easy biopsy on that and I’d be on my way. Sure enough, she agreed that pearly bump had to be checked, but she wasn’t about to let me out of there that easily. Fair skinned, blue-eyed and blond as a kid put me at risk anyway, but I might have overdone it. SPF stood for ‘sunny pool fun’ in those days. I remember layering on mineral oil and that other stuff that magnified UV rays and toned your skin copper. If sunscreen existed in the sixties, I didn’t know about it and would have ignored it anyway. I wanted to look like George Hamilton. Backpacking the high Sierra was my favorite getaway then. Two miles high, bathing unprotected skin in unfiltered sun. It’s a wonder I have any left. I remember my hiking buddy, Monroe, cackling when I dove into a freezing mountain lake after a hard day’s sunburn. My seared forehead split open like a watermelon dropped on a summer sidewalk. Sure, I use SPF 50 these days, but the damage done then supports a lot of doctors now.

Using an ink pen, Doctor Wu circled some spots and put Xs over others. She finished two games of Tic Tac Toe across my forehead, winning both. Her assistant Jimmy brought her a spray can of liquid Nitrogen, which she used to blast the indelible Xs, all eleven of them. We all know that water freezes at 32 degrees Fahrenheit, and holding a piece of frozen water against your bare skin is something doctors warn you not to do. But those same doctors will spray your skin with liquid Nitrogen, at minus 320 degrees Fahrenheit. That’s 342 degrees colder than ice. Does this make sense? Played on your head, it gives you one hell of a headache. And it doesn’t even come with ice cream.

While I was regaining consciousness, my doctor crept away to freeze someone else’s brain, and Jimmy took over. Jimmy looks about 16, though he claims a university degree. It must have been in applied sadism. He told me he was going to numb those circled spots so Doctor Wu could slice chunks out for biopsy. He said it would only take three or four injections per spot, and only the first of each would hurt. “Of each?”, I asked, “How many are we talking about?” “Six”, he answered cheerfully. “Six?”, I repeated incredulously. I had never had more than two at one time. Jimmy prepped me for painless slicing by painfully sticking a needle into my ear, face and scalp some 18 times. To take my mind off this, he told me more about himself. The one thing I remember is he was born in China.

Doctor Wu’s biopsies were indeed painless. Between the liquid Nitrogen bath and Jimmy’s needle, I had lost all feeling from the neck up. However, I could still smell. I realized this when Jimmy plugged a soldering iron into an outlet and began burning my wounds to stop the bleeding. An iron made in China, no doubt. With that and some bandages, I finally escaped. I’m still waiting for the results of the biopsies. If any are positive, I’ll have to go back for Mohs surgery. By then, I hope we’re picking on Iran again.

I had another tomato treatment today, and it wasn’t any more fun than the last four. Dermatologists or their proxies do this to their patients, but Jack Bauer and the CIA should give it serious consideration. It could obsolete water boarding. Getting a tomato treatment is pretty simple and requires no water. The doctor decides which part of your body wants to become a tomato, and then he leaves for golf. In my case, he thought my scalp, from my forehead to my nape, wanted to become a tomato. He came to this conclusion because my scalp was peppered with little rough bumps. These little bumps are called actinic keratoses, which are mildly annoying, but which can evolve into squamous cell cancer, which is a lot more annoying. Turning your head into a tomato is pretty annoying, too, not to mention painful. On the other hand, I had a small squamous cell cancer removed from my neck once. Before the doctor called it a day, she had subjected me to four consecutive Mohs surgeries and let me look at the large open hole before she sewed it up. The four surgeries were easier than looking at the hole and wondering how she could possibly close it. The thought of having a hundred of these holes in my scalp was what motivated me to take the tomato treatment.

After the dermatologist left for golf, one of his distractingly attractive assistants entered the treatment room. She pulled a metal tool that looked like a miniature garden hoe out of a scabbard, and began scraping my scalp as if she were clearing weeds in caliche. I winced now and then, but repeated only my name, rank and serial number. She furrowed her brow and looked around the room. Her eyes settled on a bottle of acetone, and I broke out in a cold sweat. Surely she wouldn’t be thinking of putting acetone on a newly-scraped scalp? But she was, and she did, rubbing it in with vigor and a pot-scrubber. I was ready to tell her everything, but I couldn’t speak. She smiled, re-corked the acetone and picked up a jar of chemical paste labeled Metvixia. She glanced at the hoe, but chose a tongue depressor instead, and began applying the mixture to my raw scalp like a bricklayer. Next, she found a dispenser of Saran wrap. She peeled off three feet of the clear plastic and wrapped the top of my head, from forehead to crown. Eyes watering and still speechless, I was hoping she would cover my nose and mouth, too.

So what is this stuff? Metvixia (methyl aminolevulinate) is selectively absorbed into actinic keratosis or cancer cells where it is converted into porphyrins, photoactive compounds that are sensitive to light. After an absorption time of three hours, the patient is exposed to a specific wavelength of red light for about six minutes, during which time the porphyrin-loaded cells are destroyed in a molecular reaction. The process can be uncomfortable at best or burning and painful at worst, depending upon how many ‘bad’ cells are being destroyed, but the key words here are ‘bad cells’ and ‘destroyed’.

After sitting around with your head encased in Saran wrap for three hours, six minutes would seem to be a minor epilogue. However, once your eyes are covered and you’re in the dark, holding a rubber hose that ejects frigid air to play on your head, time slows. When my fifth treatment entered the cell-destruction stage, I knew what to expect, and time still seemed to stand still. My scalp began to burn and pain asserted itself in spite of my pitiable efforts to put the fire out with that undersized cold air dispenser. Not unlike spraying a four-alarm blaze with a garden hose. When the bell finally rang and the hot light died, I was de-goggled and released. Afterward, hidden from the sun for a couple of days, my face and scalp turned into a tomato.

Things were once worse, though. My first treatment at another clinic used Levulan, a similarly-acting, but different chemical. The light-exposure part of that treatment lasted eight minutes, and I was given a tiny, hand-held battery-powered fan to cool my blistering head. Even a Navy SEAL would have talked.

Here’s something fun to do when you’re bored in Mexico: Listen for church bells (this won’t take long), and when you hear them, try to figure out what they mean. If you do, let me know.

They always seem to start out with two really loud clangs, I guess to get everyone’s attention, or maybe just to wake up the dogs that sleep all day so they can bark all night. The double-clang is then followed by an unpredictable number of spaced clangs.

This doesn’t seem to have any connection to the time, since church bells can ring at 4:16 PM or 6:50 AM, or any other time. At first, I thought the church’s clock might just be off. After all, most of those clocks probably date back to Pancho Villa, and moving oversized clock hands can’t be easy, either. But there still seems to be no connection. When bells ring at 6:50, for example, they don’t ring seven times. Instead, you hear the two-clang wake-up followed by something like thirty-seven clangs. If you’re thinking this could be thirty-seven O’clock in Mayan time, remember these bells are all in Catholic churches. I’ve also wondered if they could be a community warning, like for an air-raid or a fire. but you rarely see an airplane in Mexico and something is always burning, so that doesn’t work.

Thirty-seven, by the way, is not just some random number. I’ve counted these clangs a lot, as you can probably guess, and I hear thirty-seven clangs more than any other number. In fact, I’m sure no other number appears with the same frequency. Just for the record, I have never heard forty-eight or sixteen.

Sometimes, especially in towns with lots of churches like Guadalajara, you get treated to variations. One day I heard the usual double-clang wake-up, followed by a very melodic carillon. This was the only time I ever heard this, though, and even it was followed by thirty-seven clangs.

Speaking of Guadalajara, I took a city bus tour of the place, which was very informative. The information all came over a loudspeaker, so I couldn’t ask any questions. But the anonymous guide did talk about church bells a little. He didn’t solve the mystery of the bells, but he did point out one of the churches with a tall bell tower and a clock. When the bells in this church toll, the twelve apostles (well, twelve facsimiles) rotate around the top of the tower. Like cuckoos.

I need to get this church bell thing solved soon, since there are other puzzles in Mexico that need attention. For example, why does the garbage truck in San Miguel come on Friday one week, then Wednesday the next, Tuesday a week later and then not at all for two weeks? I’m working on it.